Check in

Remember what matters:

Spirit, authenticity, justice, words.

Do less. Live more. Know that you are loved.

The news biz

~It’s complicated~

Back in 1967, when I was 17 years old, I landed a part-time job as the Saturday proofreader at the Tulare, Calif., Advance-Register. The newspaper published six days a week, so an extra body was needed to cover the sixth day.

I got the job because I scored highest on a spelling test. I was good at spelling because I read a lot. I remember one of the words I missed on the spelling test was kidnapped, because of that time AP style spelled it with only one “p”—“kidnaped.”

At that time, the Advance-Register was a hot-lead operation with a lithographic press. The back shop had two sprawling Linotype machines, operated by men who stroked the keys as if they were petting kittens.

There was hot lead everywhere, as the Linotypes created type a line at a time from melted lead. Ink was everywhere, too. All of my clothes were stained with it.

Galleys were created when the columns of type set by the linotypists were inked and transferred to newsprint. These were what I read, looking for typos. My reference was a small book that showed where words should be hyphenated at the end of a line. The typographers often guessed wrong.

A newspaperman’s movie

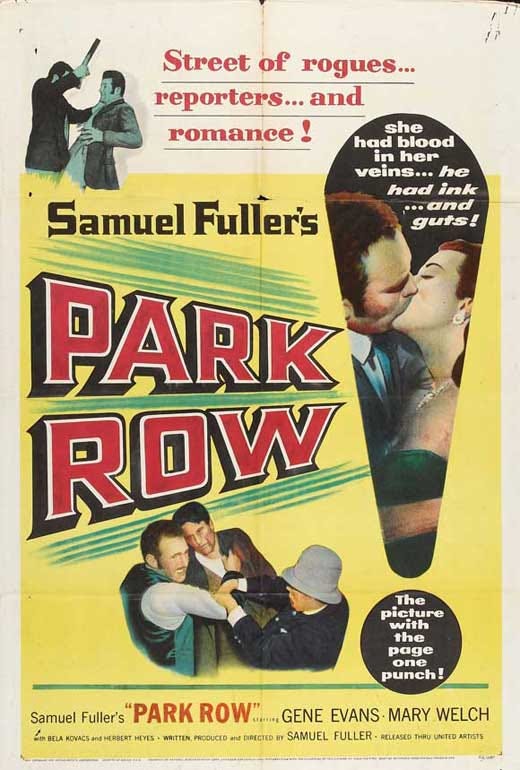

I was reminded of those early newspaper days by Park Row, a 1952 movie written, produced and directed by Samuel Fuller. It depicts life in the 1880s on Park Row, a street in New York where statues of Ben Franklin and Horace Greeley smile avuncularly on the many newspapers that vie for attention there.

Other godlike portraits in the newspaper office depict James Gordon Bennett, Sr., founder of The Herald, and Henry Jarvis Raymond of The New York Times. They are gone, but Charles Anderson Dana of the Sun and Joseph Pulitzer of the World are still in the world in the 1880s. “Dead or alive, they’re still the best publishers on Park Row,” says the movie’s heroic newspaperman, Phineas “Mitch” Mitchell.

The plot isn’t as important to me as the bits of newspaper lore. In one scene, Mitchell uses a saw to carve out a “slot,” the inside of a U-shaped desk.

It’s not shown this way in the movie, but traditionally, copy editors would sit outside, along the “rim” of the U, and the “slot” or supervising editor, would move up and down the inside on his rolling chair, taking their marked-up copy, checking the headlines, and passing it on, via a copy boy, to the compositors.

The physical “rim” and “slot” were gone by the time I got to theThe Oregonian’s copy desk, but the terms and roles still existed. Instead of handing stories to copy boys, slots would send them to the back shop via pneumatic tubes.

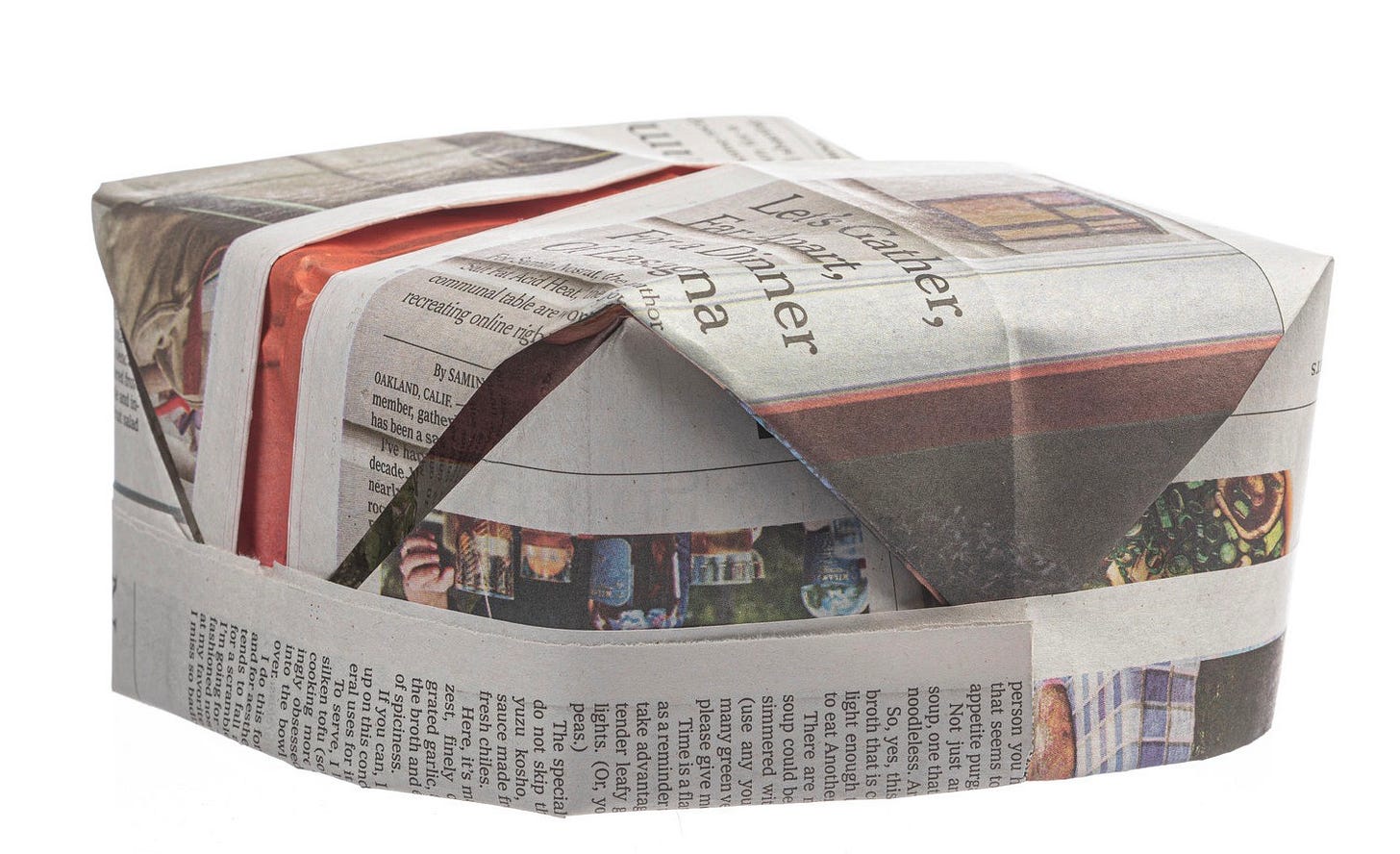

Shades and hats

The men in the movie wear two types of newspaperman head gear—eyeshades (probably green, though this is a B&W film) and pressman’s hats made out of sheets of newspaper. These were commonly worn far into the 20th century by press workers in a (mostly vain) attempt to keep the ink out of their hair.

You can make your own.

All the characters fit to print

The characters in Park Row are vintage newsroom figures. There’s the lovable shoeshine boy who becomes the printer’s devil. The speedy compositor who doesn’t know how to read or write: he just arranges the type by shape. The kindly old reporter who writes notes on the removable paper cuffs of his shirts. Mitchell, the noble publisher/editor with high journalistic standards.

The woman who publishes a rival paper never really poses a threat to Mitch, and anyway, she turns into gooey caramel every time she is around him. Like many writers of his time, Fuller didn’t have a clue how to handle female characters.

And, finally, there’s Ottmar Mergenthaler, a German inventor who is putting the final touches on his typesetting machine, soon to be christened the Linotype. He just happens to be working in the Globe newsroom on Park Row. The real Mergenthaler invented his Linotype in Baltimore.

A better way to type

In college, I parlayed the knowledge gleaned from the Advance-Register’s newsroom into various jobs as a computer typesetter. It paid way better than plain-vanilla typing, and was easier to boot.

Using a keyboard, I generated punched paper tape that was fed into a machine that pulsed beams of light through a rapidly spinning disk onto photo paper that could be waxed on the back side and stuck to a page. That typesetting machine was made by the Mergenthaler Corp.

I hated typing papers on a manual typewriter, because it was such a pain to correct errors. The beauty of computer typesetting was that you could fix typos on the fly.

Plus, having learned to code headlines gave me a leg up when I applied to The Oregonian. The paper had just switched from hot lead to cold type. Nobody cared whether I could write a headline; they were impressed that I could code one.

Upper case

This freedom from having to correct mistakes made me eager to try microcomputers when they first appeared in the early 1980s. I bought an Apple 2+ in 1982.

All the words on the Apple’s little green screen were in CAPITALS, so I had to use a tiny clip to modify the wiring of the computer to make the display show both upper- and lowercase letters.

And that brings me to two journalistic terms that most people use all the time without knowing their origin: upper case and lower case.

When a compositor sets type by hand, all the capital letters are in one place—the upper case—and the small letters are closer to hand, in the lower case.

It’s a wrap

Okay, one more newspaper term.

— 30 —

means

The End.

It was always typed with two dashes on each side, but modern word processors blend those into em-dashes, which you see here. An em-dash is the width of a capital—that is, upper-case—M. An en-dash is the width of an N.

Okay, this time it’s for real, and I’m moving on to a completely different concept.

—30—

Mangoworld

~Another metaphor for living~

Cutting a mango is a messy business, unless you know the secret: Cut the flesh away on both sides of the wide, flat pit. Then, holding a half in your palm or balancing it on a counter, use a sharp knife to score the flesh, first in strips, then in diamonds or squares, taking care not to slice through the skin.

Next, pop the piece inside out. The squares stand separated and you can easily slice them from the skin with a sharp knife.

Life is a mango, my friend

Popping a mango: Life is like that. Living with MS is like that. Either can be messy and disorganized. Or you can learn to harvest the good the way you harvest the fruit, popping life, or the disease, out of its shell, ready for a fresh start.

I let myself be vulnerable enough to turn my life inside out like that. “Let me see this differently,” I ask the Universe quietly when things are not working out. Sometimes a subtle shift in perspective can reduce stony mountains to gravel.

So, Mangoworld: A place where we can wear our hearts on our sleeves. As we pop our lives inside out, nothing remains hidden. Our secrets become our pleasures, the delightful surprises of newness that we offer one another as we come together.

I have more to tell you about exploring Mangoworld, but let this short description be your introduction to a new and exciting place.

Disability writing

This poem was written many years ago, when I visited my younger daughter, who was in college in the Boston area. (“Not much of a college town,” is the line about Boston in the mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap.)

In those days I had mobility undreamed of now. I could walk with just one cane! Today, my touchy balance won’t let me walk even with two canes. I have to use a walker or ride my mobility scooter.

Stumble Song

~Visiting Boston~

It’s not the uneven, the beautiful, the red brick of quaint old pavement that trips you. But your own body betraying you, Waiting for an uncoordinated moment to drop the foot, scuff the shoe. Each time it’s new, never expected-- never quite what went before. Your ankle aches with many recoveries from stumbled steps. And then you trip, not on bricks, but on a crosswalk painted on asphalt. The street is busy. A policeman leans out the window of his car: “You OK?” he yells. But he stays inside as you scramble up, pushing your skirt down to cover the brace, unhurt yet bruised all over. What will be the last stumble? The last thing, ever— Will it be a last step Or a last stumble? But of course, It’s not up to you. It comes from a part of you That you cannot know. You can’t know what You only know that Something Will happen When it happens. Stress, you think, Stress does it, Slows the leg, Brings the stumble. You think about How your hand hurts From gripping the cane. You think about the sky. These are not stressful thoughts. They just are thoughts. But the stumble comes, Anyway, in a hotel hallway, when your foot catches on the nap of the carpet And you fall down.

Check out

Please, keep writing. Keep reflecting. Trade in a few minutes of TV viewing for simply staring out the window and letting your thoughts flow calmly.

In his epic poem Paterson, William Carlos Williams writes often about writing. Here are words I found at random (Book 3, Chapter III, Page 181 in the New Directions paperback version):

It is dangerous to leave written that which is badly written. A chance word, upon paper, may destroy the world. Watch carefully and erase, while the power is still yours, I say to myself, for all that is put down, once it escapes, may rot its way into a thousand minds, the corn become a black smut, and all libraries, of necessity, be burned to the ground as a consequence.

Only one answer: write carelessly, so that nothing that is not green will survive.

Coming up

I’m not much of a sports fan, but I watch as much as I can of the World Cup. It only comes around every four years, like the Olympics. I don’t watch soccer otherwise.

If I catch as many games as I plan to, it might cut into my writing time. The fatigue and physical slowness of MS already keep me from executing thoughts and tasks as easily as hale people. But it’s been four years since the last go-around, and the disease has progressed, so I’m not sure just what to expect.

So, you might see an update next Monday. You might not.

—30—

Great posts and I really love the poem. I wish it could reach a wider audience.

Fascinating stuff, Fran. Thanks.