Check in

The sublime in the mundane

Being mindful is paying attention. When you pay attention, you notice things. Like these signs on a door in Avignon, France. Publicitè interdite translates to “no soliciting.”

Shadow words

Some time ago, I started collecting shadow words. These are words that seem negative but which, if you unwrap them to their essence, contain a germ of good.

Consider the shadow word “mindless”:

You cannot think “mindless” without being mindful. This shadow word contains its own sun.

As is so often the case, the obverse of the shadow word is the one we want to chase, waving the butterfly net of our understanding. We banish “mindless” by pursuing “mindful.”

To be mindful is to live in the moment. Awareness keeps us grounded. We are here, now, doing the work of the day.

Yet how many times I have done a task mindlessly, not being present, not thinking about what I am doing. On autopilot.

I am driving and I suddenly realize I have taken the familiar route when I had planned on taking a detour to run an errand.

I get to work and realize my lunch is sitting in its bag on the kitchen counter.

Or—and how often does this happen to you?—I move to another room to pick something up or accomplish some task. And I can’t remember what it was.

The abyss of consciousness

An unfocused moment, and intent is annihilated. It takes only a moment of inattention. Mindlessness begets forgetfulness.

Cultivating mindfulness takes time, habit and concentration.

Mindlessness, on the other hand, takes no effort at all. It produces after its own kind.

An action, an experience undertaken mindlessly is not really experienced at all.

It happens in a vacuum.

Therefore, strive to be mindful. Remember, be present.

Cornball

Blueberries are coming on in Oregon, so it’s not surprising to run into one at the Hillsdale farmers market.

I asked her (she’s a female blueberry) what her name was, and she, coyly, would only give her first name: Ima.

I venture a guess. “As in Ima Blueberry?”

“You got it,” she says with a deep purple wink.

Walking road trips

I’ve read two “road trip” books this summer that are about walking: The Salt Path, by Raynor Winn, and Wild, by Cheryl Strayed.

Winn and her husband, Moth, walked the 630-mile South West Coast Path in southern England, beginning in Somerset and running through Devon, Cornwall and Dorset.

Strayed, alone, braved the Pacific Crest Trail from the Mojave Desert to the Bridge of the Gods over the Columbia River.

Both books were best sellers.

Parallels

The walkers undertook their journeys at crossroads in their lives. Strayed, still in her 20s, was working through the untimely death of her mother and the end of her marriage. She was staking out her career as a writer.

The Winns, Raynor and Moth, were newly homeless, having lost their farm, their life’s work, in a botched judgment. Additionally, Moth had been diagnosed with a rare neurodegenerative disease, and his vitality was failing.

Losing companions

Not long before Ray and Moth were forced to leave their property, a beloved ewe, a stalwart companion, died. She seemed to sense that her time was done and her humans were leaving.

In a wrenching scene, Strayed writes about the agonizing death of her mother’s horse who had to be put down. It did not happen easily, and the scene is powerful and painful.

Authenticity

Cheryl Strayed is unflinchingly honest about her very human frailties, about the way she has abused her body, about roiling emotions.

Ray and Moth Winn are prickly but lovable: dotey, as my Irish sister-in-law would say.

Wild

Cheryl Strayed is from Minnesota, like me, and spent time in Sioux Falls and Portland, as did I. But her experiences leading to the decision to hike are foreign to me: experiments with drugs, being ambitious to write for writing’s sake at an early age, the untimely death of her mother (mine lived to 97).

But once she’s on the trail, she’s Everywoman. Her pains are your pain—and there are many, from sores where her overladen backpack chafes her to unending pain from ill-fitting hiking boots.

But what shine through is the honesty of her thoughts, the authenticity of her reactions. She describes incredible beauty along the trail, but the true journey is internal. Nature turns her inside out.

Packing

Strayed packs—overpacks, repacks—her backpack, all the while unpacking her own life—fears, foibles, relationships. She examines all these things in the solitude of trail and tent. Amid ineluctable beauty, she grows.

It’s a lot about comfort and discomfort. About losing toenails and running out of water. Being totally sick of trail mix and in love with Snapple lemonade. It’s honest, authentic, heartfelt.

In an interview with Strayed for her Substack publication Beyond, Jane Radcliffe writes:

Cheryl has a knack for acknowledging what is. I mean, really-really-really acknowledging what is, no bones about it. And then greeting it with clarity, kindness, humor, and the possibility of dismantling everything you know for a healthier, more truthful existence.

In Wild, Strayed writes about being by herself:

Alone had always felt like an actual place to me, as if it weren’t a state of being, but rather a room where I could retreat to be who I really was. The radical aloneness of the PCT had altered that sense. Alone wasn’t a woman anymore, but the whole wide world, and now I was alone in that world, occupying it in a way I never had before. Living at large like this, without even a roof over my head, made the world feel both bigger and smaller to me. Until now, I hadn’t truly understood the world’s vastness—hadn’t even understood how vast a mile could be—until each mile was beheld at walking speed.

The Salt Path

The elements are no kinder to the Winns than they are to Strayed. Strayed battles heat and cold, snow and rain, thirst. The Winns are often soaked to the skin, even in their inadequate sleeping bags in their inadequate tent.

Camping is its own issue. Outdoor camping is banned in Britain, so they have to hide the tent amid the gorse. They are forever being chased out of campsites because they can’t afford the overnight fee.

But they, too, find riches, some of it in companionship:

On the trail, they encounter a small woman with a very long braid and a border collie who asks where they are headed. Ray explains they’ve been camping.

“I can tell,” she says, “you have the look.”

“The look?”

“It’s touched you, it’s written all over you; you’ve felt the hand of nature. It won’t ever leave you now; you’re salted. . . . People fight the elements, the weather, especially here, but when it’s touched you, when you let it be, you’re never the same again.”

A bit further on, Winn acknowledges being touched.

. . . something in me was changing season too. I was no longer striving, fighting to change the unchangeable, not clenching in anxiety at the life we'd been unable to hold onto, or angry at an authoritarian system too bureaucratic to see the truth. A new season had crept into me, a softer season of acceptance. Burned in by the sun, driven in by the storms. I could feel the sky, the earth, the water and revel in being part of the elements without a chasm of pain opening at the thought of the loss of our place within it all. I was a part of the whole. I didn't need to own a patch of land to make that so. I could stand in the wind and I was the wind, the rain, the sea; it was all me, and I was nothing within it. The core of me wasn't lost. Translucent, elusive, but there and growing stronger with every headland.

And then, the bittersweet understanding that the end was near:

We walked painfully slowly, stopping to look around every few minutes, excited to get to the end, but willing it not to come.

That sentiment, actually, was how I felt while reading this book.

Guidebook

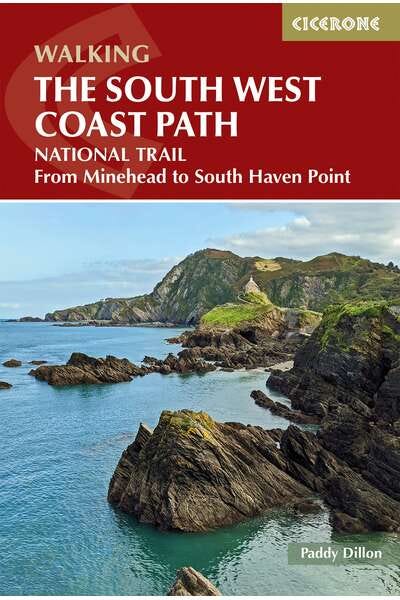

Walking the South West Coast Path National Trail from Minehead to South Haven Point, by Paddy Dillon, is like a third character in The Salt Path. The Winns consult it continually.

Curious, I borrowed this guidebook through interlibrary loan, since the Multnomah County Library doesn’t have a copy, and it was too expensive to buy. But holding this handsome volume, with its waterproof cover, fold-out maps, cheerful text, pretty photographs and detailed illustrations, I can understand why the Winns so valued it. It has intricate details about every step of the path—what to expect, which path to take, where to eat or do your laundry.

I’m sorry I have to send it back to the Seattle Public Library.

Books along for the ride

There’s a guidebook in Wild, too: The Pacific Crest Trail, vols. I and II, the second volume waiting for Strayed at a stop along the trail.

Every morning, Strayed carefully burns the pages that cover where she’s been, to lessen the weight of her pack. I can’t imagine doing that to Dillon’s beautiful book.

Both parties have favorite books that they make room for in their heavy backpacks. Moth Winn treasures Shamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf. He even picks up a few pounds by standing on a street corner and reading, with gusto, from the book. With his shock of white hair and deep-set eyes, he resembles King Lear.

American guidebook

In her vastly overstuffed backpack, Monster, Strayed packed the Pacific Crest Trail guidebook, a book on how to use her fancy compass, William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (itself about a road trip), and Adrienne Rich’s The Dream of a Common Language. I’m impressed by the Rich book; these poems are not easy and Cheryl is only 26.

Other books come and go, including James Mitchener’s The Novel. Pieces of that book are immolated the next morning, too.

Every reason to read

Good books become a part of you. Both these books touched me deeply, and changed my outlook on life and experience.

I hope you have time to pick up at least one of them and enter a world of beauty, introspection, discovery and change.

Poem

Turning away from nature

Even

Knock the papers on the desk, Even the edges, Tap stray pages into place, Perfectly aligned. Could our lives be like that? Measured and squared? No, no, life is messy. The quilt covering the jumbled bedclothes, The bureau shoved shut while the socks complain, A junk drawer, Where nothing can be found Until days, weeks After you needed it. How can we stand our messy lives? Pizza boxes, soda cans, Popcorn behind the couch— Even the cat won’t eat it. Parakeet droppings We hardly notice. We’re used to dirty towels. Why take off shoes upon entering If there’s mud on the floor already? Dirt stains our lives. Clutter undermines our resolve. . . . Forget all that— Let’s eat popcorn!

Dalgona coffee

Summer is a good time to enjoy this treat, a fluffy, sweet mousse that is equal parts instant coffee, sugar and hot water. It’s easy to make.

Put the sugar, coffee and hot water in a bowl and whip it until it forms soft peaks, like egg whites.

I’ve made it with a hand whisk, but a milk frother works well and is easier on the arm.

Spoon some of the mousse on top of hot or cold milk, or mix it in.

The rest keeps in the fridge until you can’t stop craving it and eat it up.

Chinese film star

Wikipedia says the beverage originated in Macau, later spreading to South Korea, where it was dubbed “dalgona” because it resembled a Korean candy made from sugar and baking soda. The honeycomb crunch is like peanut brittle.

The legend is that Hong Kong film star Chow Yun-fat (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) was seen drinking the concoction in a coffee shop on the Macau island of Coloane. Folks started asking for “Chow Yun-fat coffee,” and a craze began.

Nix on sugar

I’m trying to limit sugar, so I made a batch with Swerve, a sugar substitute that has the heft of sugar. Swerve is an interesting product that caramelizes like sugar and can be used in baked goods, but I may not buy it again. It’s made with sugar alcohols, which can upset some people’s digestion (though not mine). I just find I don’t like the idea of any artificial sugar.

I loved sugar all my life, but a diagnosis of pre-diabetes means I shouldn’t eat it anymore. I accept that.

If I don’t eat anything sweet at all, including stevia or other non-sugar sweetener, the massive craving for sweets calms from a raging roar to a quiet buzz.

My body thanks me. But I do miss Mars bars.

Checkout

This is from “The Four Quartets: The Dry Salvages” by T. S. Eliot. It’s quoted in The Tao of Psychology by Jean Shinoda Bolen.

These are only hints and guesses,

Hints followed by guesses; and the rest

Is prayer, observance, discipline, thought and action.

Why write?

I keep urging my readers to write daily. Why would I do that? Why write, anyway?

Well, it’s not for the money (though thank you, paid subscribers!). You could probably make more tending bar.

It’s not the sharing, either, though I’m blessed with this platform where I can write for others to read.

No. There is only one real reason to write.

And that is for you.

Writing as a daily exercise will transform you. I know, I keep saying this, but it’s true.

Till next time.

—30—

Walking in the forests around my home in Truckee was an exercise in recalibrating my rhythm. The beat of my boots on the earth in tempo. Thoughts of bears or lions. Hearing squirrels chatter with indignation as I passed beneath their trees. I had many an epiphany while walking. One day when I was due to go to work in the library, I felt something snap in my chest. I sat down and recalled yet another time the heated brow-beating I'd received from my boss about something she misunderstood but refused to hear my explanation. "You're not a team player!" she screamed at me. I sat on that rock, listening to her voice again and again. I got up to finish walking home, picked up the phone and told them I wouldn't be coming in to work .. ever again. Such is the power of walking. It recalibrates your rhythm.

I read The Salt Path after seeing it recommended by Cheryl Strayed. Loved it. It made me want to go walking for days on end, too.